Paintings from the National Academy of Design in The Fine Arts Conservancy lab.

William Merritt Chase, The Young Orphan, in The Fine Arts Conservancy, photography room, before removal from its frame.

The National Academy of Design, the esteemed institution of American Art, received a donation from Tru-Vue of their Optium Museum Acrylic for five works of art.

When we were contacted by Jeremiah McCarthy, Curator of the National Academy of Design, to fit the five paintings with the Optium Museum Acrylic, we immediately knew how important an opportunity this was to help preserve paintings that are vital to the history, story and foundation of American Art. Self-portraits by quintessential artists who are the backbone to American art. To become a member of the National Academy of Design, an artist was required to paint a portrait and more times than not it was a self-portrait. Their submission portrait was the very best at that time in their career – it was a portrait they presented proudly. For their diploma piece, the artist submitted a painting, again what each artist considered to be their best at the time. These submissions were judged by their peers. The tradition continues today from its beginnings in 1825. A rich storehouse of American art. The stewardship is understood by its curators and they recognize the weight of the commitment. Jeremiah and Diana Thompson, Director of Collections, are to be praised for their goal to protect the paintings. These were selected because of their travelling schedule with the exhibition For America. Prompted by a desire for the public to know that the works of art in the National Academy of Design are for all Americans and not just for New Yorkers where it is located. The exhibition, For America was formed. It travels to venues crossing the country.

In all eight paintings which are in the the For America exhibition received the Tru-Vue, Optium Museum Acrylic – the gold standard. Tru-Vue donated the Optium for the William Merritt Chase, The Young Orphan; Thomas Eakins’ Self-Portrait; Winslow Homer, Croquet Player; John Singer Sargent’s portrait of Claude Monet and Sargent’s Self-Portrait. As we looked at the works in the exhibition and noticed others that would benefit from having Optium coupled with our desire to help with the preservation, we, The Fine Arts Conservancy, donated the Optium for Cecilia Beaux’s Self-Portrait; Alfred Bierstadt, On the Sweetwater near the Devil’s Gate; and Frederick Church, Scene Among the Andes.

Optium Museum Acrylic is now the highest quality acrylic for glazing works of art. The material has all the properties that are required for the preservation of art and then some. It is far superior to what was available a few years ago and what is on the market today from other brands. The protection from UV is at 99% which is the highest available, the clarity is unsurpassed as it does not distort delicate lines and passages in works of art and the artist’s palette remains true without color shifts that happens with other acrylic glazing, and virtually reflection free; that is just from a visual standpoint. From a practical standpoint the material is abrasion and shatter resistant, and lighter than glass, definite pluses for the handling of the material. Optium Museum Acrylic will last longer than other acrylics that are rated as framing grade.

As we removed each piece from its frame, we found modifications within the frame for the work to fit. It was not unusual to find two and three modifications as frames are frequently re-used for other works than its first intent; adjustments and alterations are made to accommodate the new piece. A frame is made either in a standard size or a custom size to fit a particular work. Through time that frame can and will likely be used to surround another work, one that might be a bit too small; strips and shams are added to the interior to make the work fit. Sometimes two and three modifications indicating that the frame has been used for more than two different sized works. It is necessary to remove all the added strips of wood and shams for the true rabbet (the area where the work rests) to be revealed. Glazing must sit within the actual rabbet of the frame not on top of strips of wood used for modifications. If not, the glazing will never be secured properly, and neither will the art.

In the near photograph the strip of wood on the frame for Thomas Eakins’ self-portrait is being removed, the light colored wood was the latest modification, the darker color wood strip beneath was a previous modification and the darkest is the original rabbet of the frame. It was important to carefully and gently release the wood strips held in place with nails so that the original frame would not be damaged.

Interior of frame around Thomas Eakins’ Self-Portrait. Releasing the top strip used for modifying the rabbet of the frame. Two modifications: the lighter colored strip and the darker colored wood underneath. The darkest is the original rabbet of the frame.

The actual rabbet of the frame. John Singer Sargent’s portrait of Claude Monet is seen in the background.

The face of a work cannot touch the surface of the glazing, there must be a space between the two. To achieve this distance the glazing and work are held apart by a spacer. The objective was to have the material of the spacer archival and its color in sympathy with either the palette in the work or the frame. The material of the spacer had to be strong enough to hold the glazing away from the work, and it could not exceed the width of the lip (the edge of the rabbet that holds the work in the frame) of the frame as it would be exposed from the front. Each of the eight works had a different solution for the spacer.

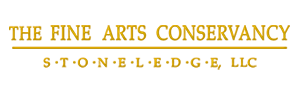

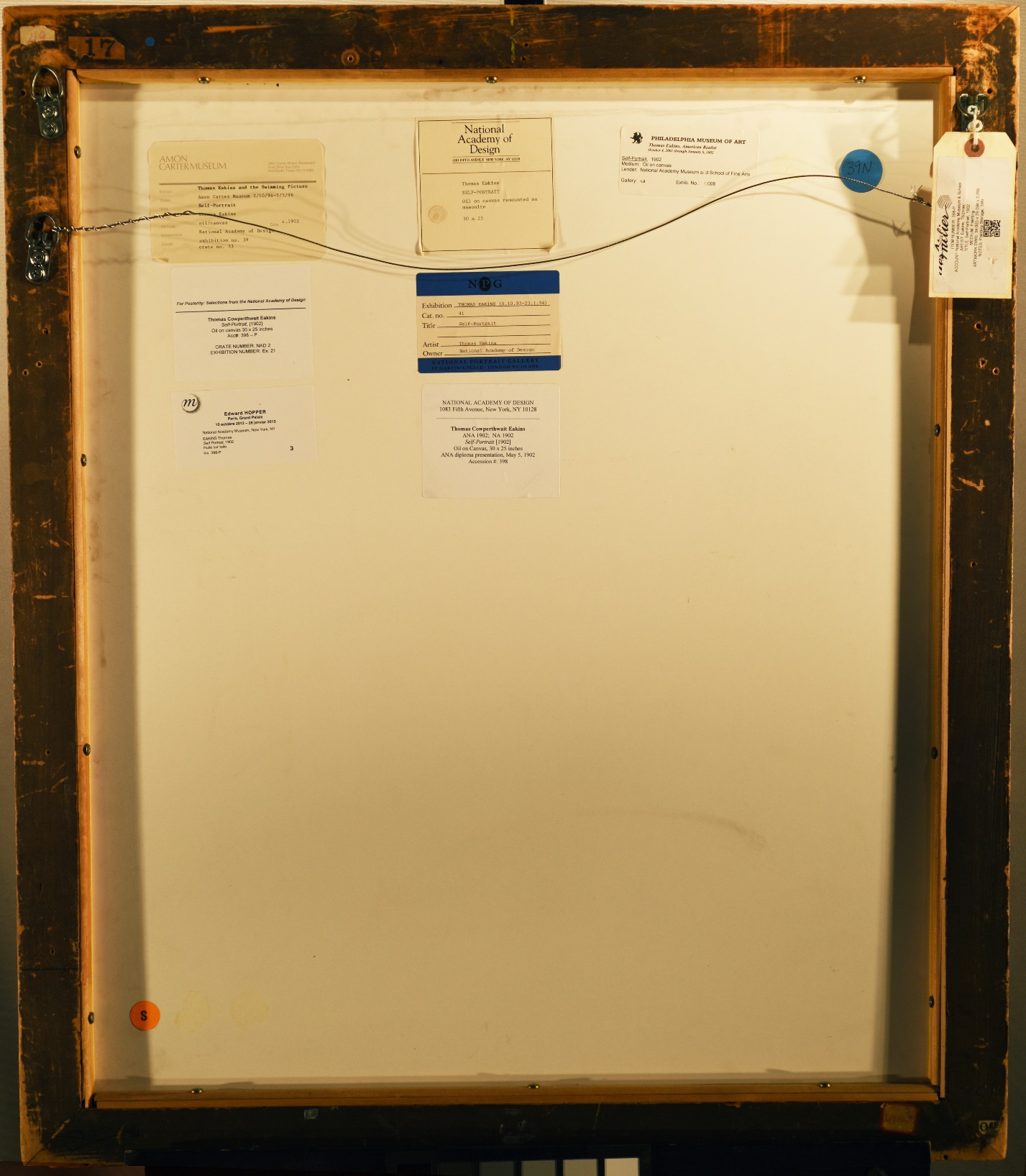

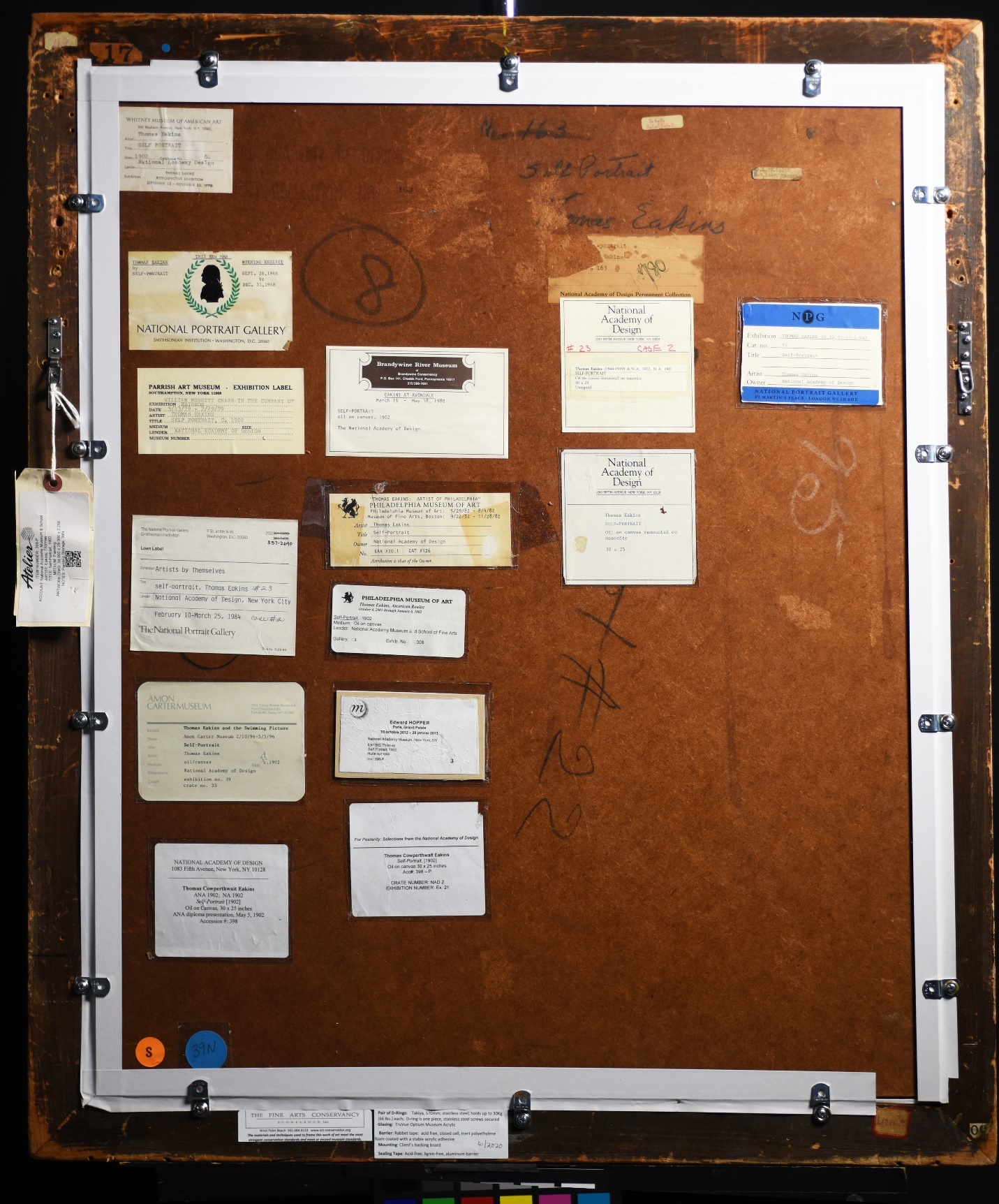

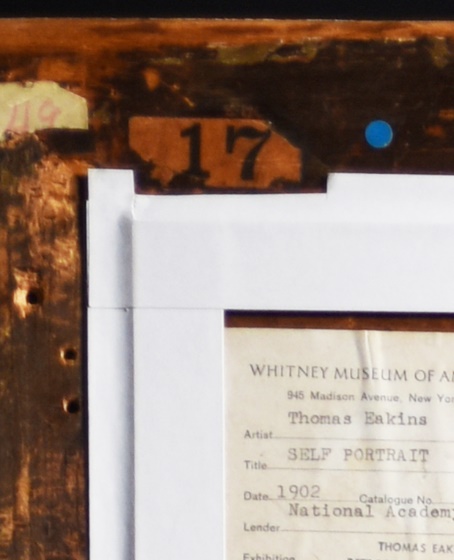

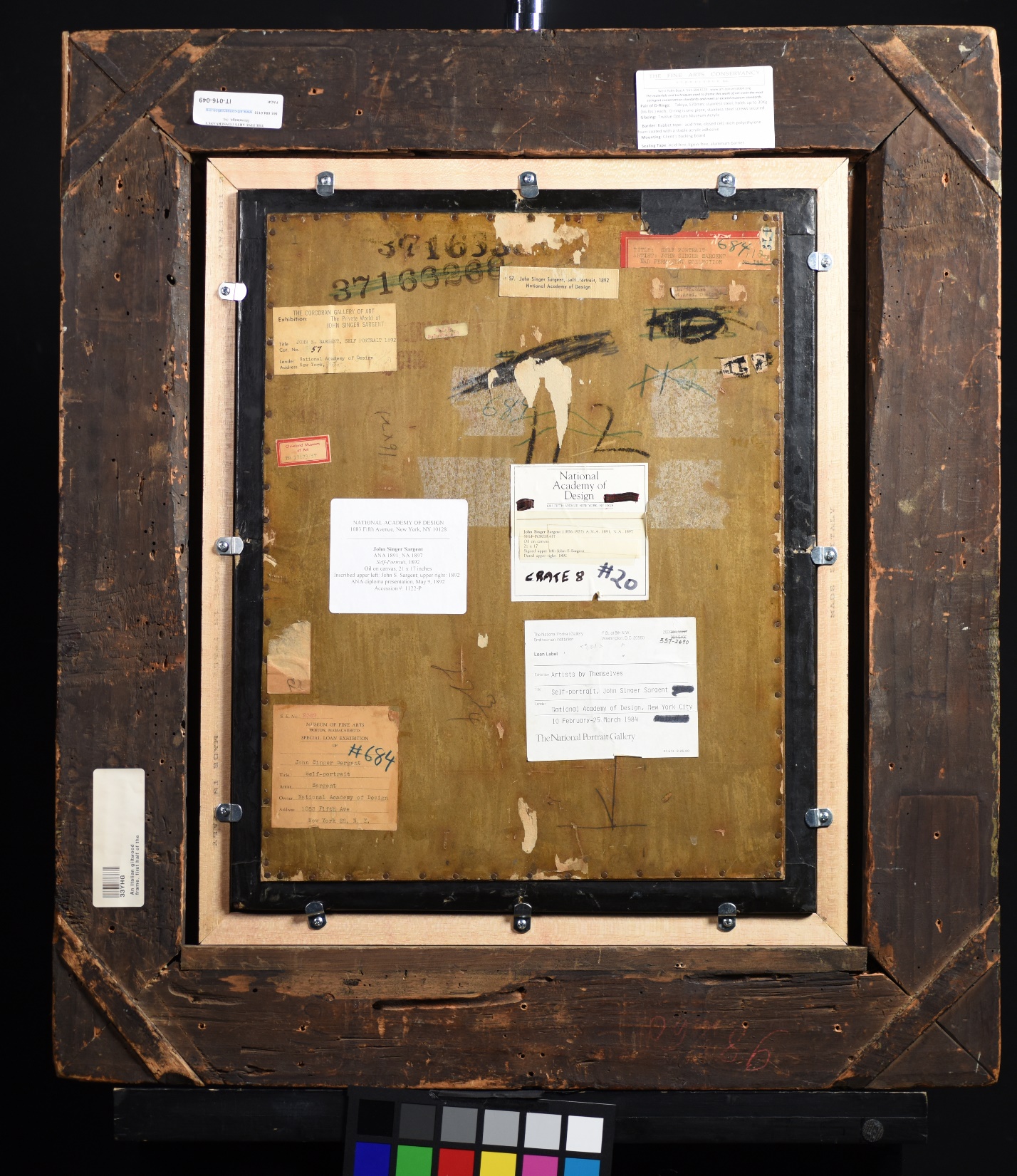

Many of these paintings have traveled extensively with the exhibition labels affixed to the backing boards. Again, over the course of time, new backing boards had been added with more labels affixed. As we removed the backing boards, we discovered previous backing boards with early exhibition labels and the National Academy of Design documentation. We replaced, where possible the opaque backing boards with acrylic so the original labels and documentation could be seen and after removing the labels from the previous backing boards affixed each one to the new acrylic. Now all the documentation can be seen. Archival tape was placed around the backing to prevent pollutants and dust from migrating into the work. The tape was cut around labels and stamps on the frame itself. See the near by photograph of the verso of the frame around Eakins’ self-portrait.

Before reframing photographic documentation of the verso, Framed

Verso of painting on board with early labels affixed

After, verso acrylic backing with labels from opaque backing board affixed and early labels on artist board visible.

Close-up of tape cut around label on frame

After framing with Optium Museum Acrylic, Thomas Eakins, Self-Portrait

All hanging wire was removed and Takiya D-rings were used. Wire becomes brittle and snaps and it is never known when it will weaken from deterioration to the point that it breaks until the painting falls to the floor damaging the frame and the painting. Then it is too late. Takiya is made with a grade of stainless steel that does not corrode over time. With its superior engineering the rings are either stamped out of a solid piece of stainless steel or welded together. The arrangement of the screws on the top and bottom of the plate distributes the weight. Because of their rated weight strength, their footprint is smaller.

Takiya D-ring on the verso of the frame for Alfred Bierstadt, On the Sweetwater near the Devil’s Gate

CLEANING- UP THE CHURCH

The varnish layer on the Frederick Church painting, Scene Among the Andes (1854)

had discolored turning a yellowish-green color which is not uncommon for varnishes. The photograph near by shows an area that was tested for the removal of the varnish. The discolored varnish is on the cotton swab. The next photograph shows the beautiful blue sky that is under the yellowed varnish. Discolored varnish obliterates the middle tones and values of the pigments making the overall appearance to be flattened as the middle tones that give the works depth are no longer visible. The removal of the discolored varnish returns those middle-values. Once the old varnish was removed, a new layer of non-yellow, museum varnish was applied.

Test removal of varnish

Test Removal of varnish

Detail of varnish removal, revealing the blue of the sky

Before varnish removal

After varnish removal

After framing with Optium Museum Acrylic, Frederick Church, Scene Among the Andes.

A TIGHTLY CONTROLLED ENVIRONMENT FOR THE INNESS, THE MICRO-CLIMATE

Fluctuations in humidity cause the support of works to contract and expand in direct relationship with their ambient environment. The support structure itself reacts to these changes by cockling and buckling; this movement triggers the paint layer to crack. The solution is obvious keep the pieces in a highly and tightly controlled environment. To prevent the fluctuations especially on fragile supports a custom micro-climate is made: creating a system that seals in the desirable humidity level so that as the work moves from venue to venue from truck to truck and under exhibition lighting the support structure is not affected by the environmental changes. George Inness’s Landscape of 1860 was painted on paper which later was attached to board, both hydroscopic. A custom micro-climate was made.

Verso, Micro-climate with hygrometer in laid into the rear board visible through the acrylic

Several layers of non-acidic fluted board are placed behind the backboard, the cellulosic mass controls the humidity in the system. All of the materials are conditioned to the correct humidity before placing and sealing with a stainless steel tape with an acrylic adhesive, the final tape is to protect the stainless steel tape from accidently being peeled back and for a finished appearance. Acrylic adhesive is key because it is the only self-adhesive which will not dry out and fail.

After framing with Optium Museum Acrylic and in its micro-climate, George Inness, Landscape, 1860

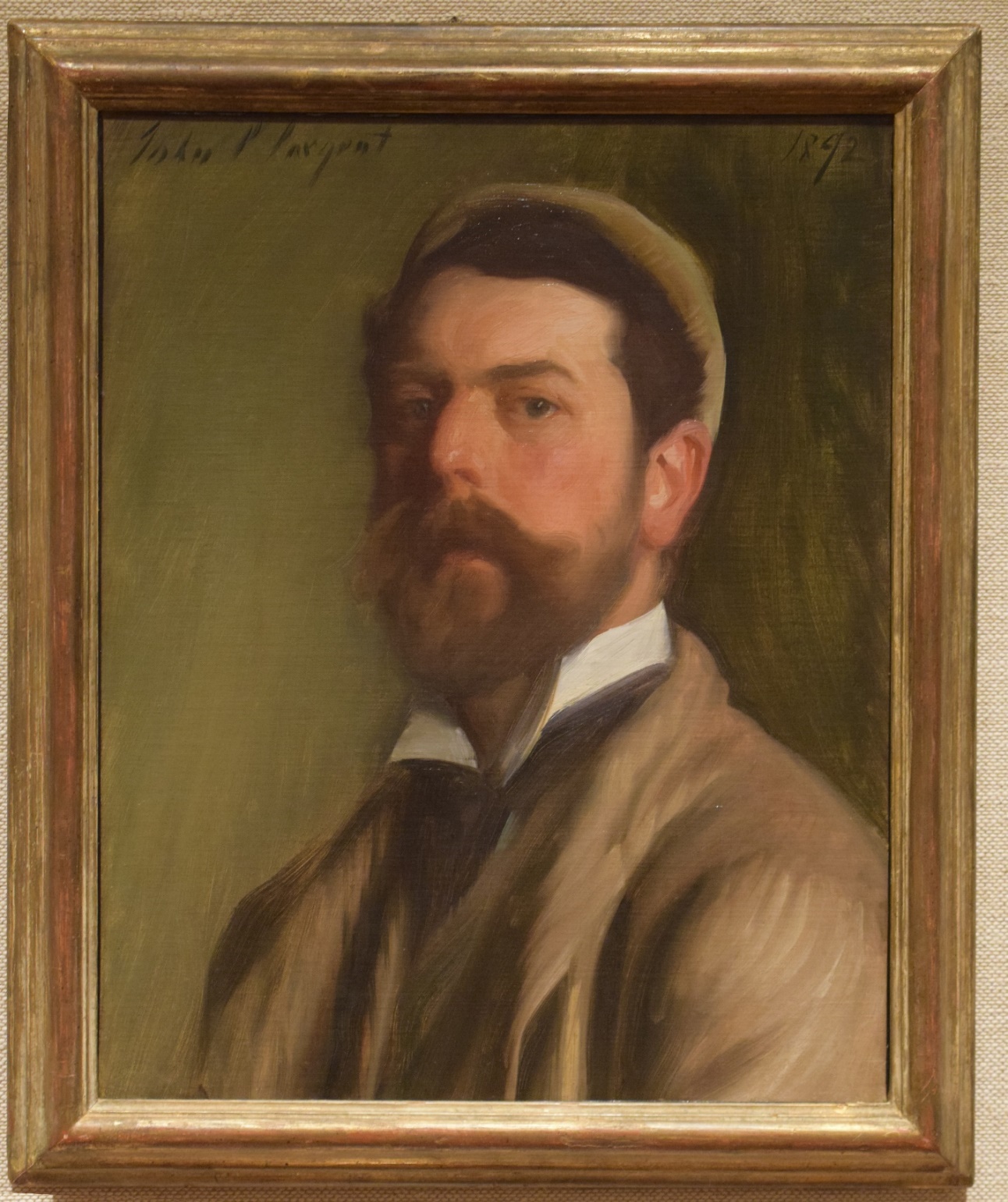

A NEW FRAME FOR SARGENT’S SELF-PORTRAIT

John Singer Sargent’s Self-Portrait of 1892 was framed in a narrow, modern version of an Italian 16th frame. From our collection of authentic period frames we had a late 16th century carved and gilded Italian frame that was appropriate for the self-portrait not only because he preferred period frames whenever he could find them and it is in keeping with his aesthetics, but also because it has the quality and scale to present a portrait of this significance.

Before re-framing, modern version of an Italian narrow moulding 16th style frame.

Italian end of 16th carved and gilded decorated with leaf scrolls in a pastiglia technique and shallow carving; a punch background.

Detail of carving and punch work in the background (circles). After the gilding a tool with a decoration is “punched” into the surface carefully so that the thin gold leaf is not broken creating a textured background for shallow carved leaf scrolls. Closeup of punch work below.

Verso of Framed Self-Portrait

Our work is finished, and our “friends” (all pictured below) are back with the exhibition, travelling for Americans to see some of the wonderful works that the National Academy of Design holds, For America. What a privilege it is to have helped with the stewardship of preserving the legacy. Thank you!

Gordon Lewis

Laney Lewis

The Fine Arts Conservancy

West Palm Beach, Florida

www.art-conservation.org

THE WORKS OF ART FROM THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF DESIGN

Cecilia Beaux (1855-1942) Self-Portrait, 1894

Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) On the Sweetwater near the Devil’s Gate, 1859-60

William Merritt Chase (1849-1916) The Young Orphan, 1884

Frederick Church (1826-1900) Scene Among the Andes 1854

Thomas Eakins (1844-1916) Self-Portrait, 1902

Winslow Homer (1836-1910) Croquet Player ca. 1865

George Inness (1825-1894) Landscape, 1860

John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) Claude Monet, c. 1887

John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) Self-Portrait, 1892